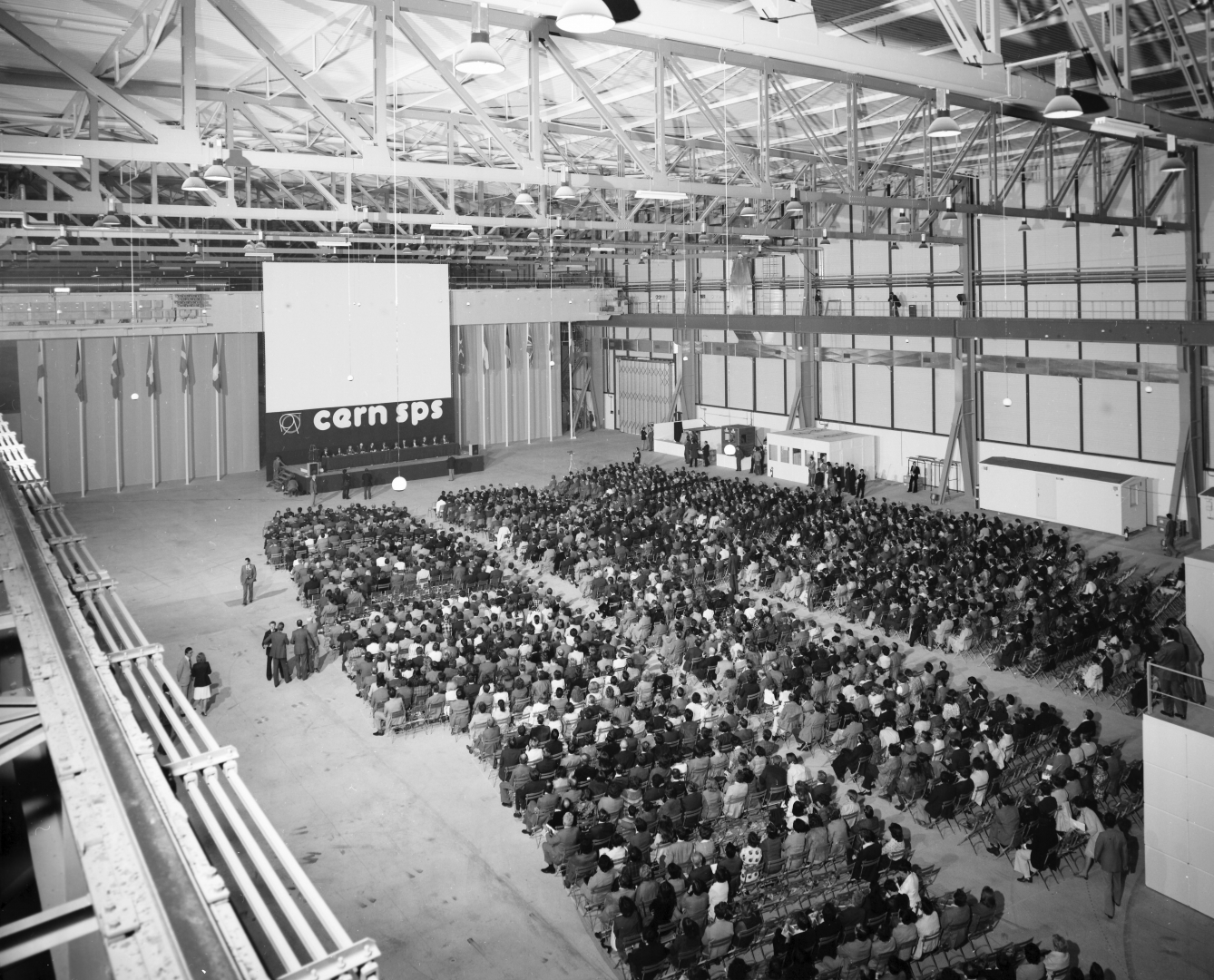

Forty years ago, on 7 May 1977, CERN inaugurated the world’s largest accelerator at the time – the Super Proton Synchrotron. The first beam of protons had already circulated around the seven kilometres of the accelerator in May of the previous year, and future research would include the Nobel-Prize-winning discovery of W and Z particles in 1983, when the machine was running as a proton-antiproton collider. The inauguration of the SPS gathered around 2000 people at CERN. A selection of brochures, press releases, photos, and audio-visual material available online in the CERN Document System helps to recreate the event.

But what was happening behind the scenes? Did you know that the organising secretary, E.W.D. Steel, universally known as “Miss Steel”, set up a massive card index to keep track of the guests, entering all the details on 6000 colour-coded cards? She also insisted on sending reply cards to the VIPs, even though treating them like ordinary mortals was considered demeaning. “The higher you go in a hierarchy, the less legible signatures become,” she used to say, as she wanted to know who the replies came from. Logistics were further complicated by differing ideas in the different countries as to what constituted an “official delegate”.

It’s all in her report, which is in the CERN Archive, along with another 1000 or so shelf metres of files filled with letters, notes, reports, rough drafts, memos and plenty more. Miss Steel’s “ant’s-eye view”, as she called it, is a trivial example, but the view behind the scenes is crucial. Without this, our understanding of past events is based solely on what was intended for public consumption, and history becomes just what was written by the winners.

Archival documents are a remarkable resource. They are the documentary by-product of human activity, the records generated by individuals and organisations over the ordinary course of their lives, and are an irreplaceable testimony to past events. For organisations such as CERN, archives provide a corporate memory that can be preserved while human memories fade. Not everything is kept, of course; in general, between 5 and 10% of the records produced by an organisation might be considered worth preserving for historical reasons.

Historic documents are precious, but they are also vulnerable. They are easily damaged or lost, and a scrawled note that changed the design concept for a project decades ago would make little sense removed from its context – the surrounding documents help us understand who wrote it, when and why.

Archives provide historical information to support ongoing activity, and the CERN Archive is consulted by researchers within and outside the organisation. Effective management of records and archives also underpins good governance, administrative transparency, the identity of individuals and communities, the preservation of mankind's collective memory, and access to information by citizens.

If you think there could be information in the CERN Archive that would be useful to you, if you know of material that you think should be preserved in the Archive, or if you are just curious to know more, take a look at our webpages or get in touch (anita.hollier@cern.ch). We’re always glad to help if we can.