CERN70: Green light for LEP

31 July 2024 · Voir en français

Part 14 of the CERN70 feature series. Find out more: cern70.cern

Herwig Schopper was Director-General of CERN from 1981 to 1988, during which time the Large Electron Positron collider was approved and constructed

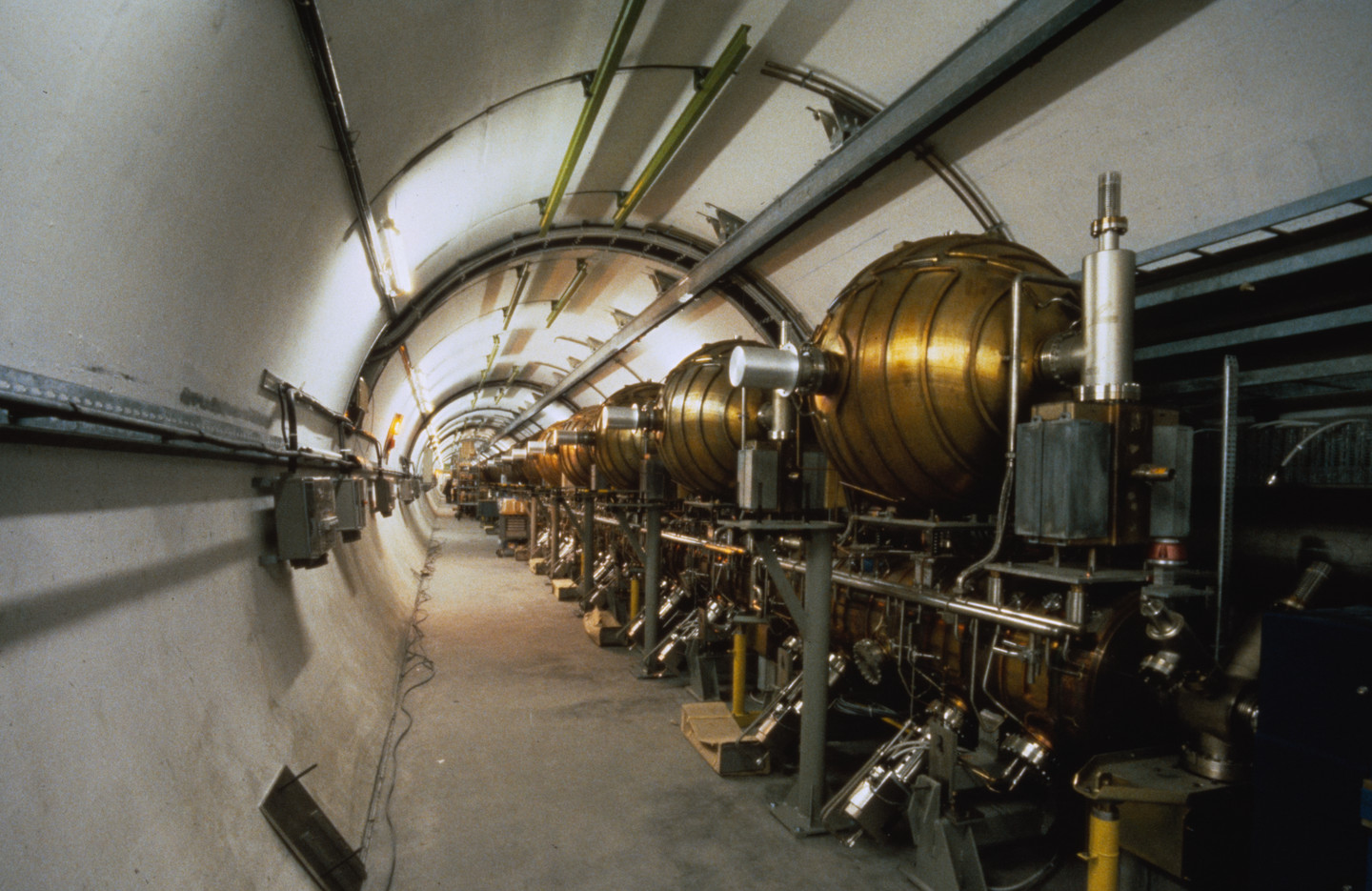

The Large Electron Positron collider (LEP) project was first presented to the CERN Council in June 1980, following the development of several concepts at different energies and lengths. The project envisaged an energy of 50 gigaelectronvolts (GeV) per beam and a circumference of 27 km, using the Proton Synchrotron (PS) and Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) as pre-accelerators.

After negotiations with Member States, a final “stripped down version” was adopted in 1981. The idea? To design LEP as an “evolving machine”: after an initial phase as a Z factory (the Z particle would not be discovered until 2 years later), LEP's energy could, in a second phase, be doubled by incorporating superconducting accelerator cavities.

On 13 September 1983, French President François Mitterrand and his Swiss counterpart Pierre Aubert launched the construction of LEP. Excavated 100 metres below the surface, with a circumference of 27 km, this accelerator was to become the largest in the world. It was the biggest civil engineering project in CERN's history, and the largest European construction site before the Channel Tunnel.

Obviously, choosing the precise location for a subterranean ring between the Jura Mountains and Lake Geneva was a far from simple task, and the route eventually had to pass along the edge of the Jura, a section where the construction work encountered many challenges. For geological reasons, the tunnel was excavated with an inclination of 1.4%, making LEP the first inclined collider. Finally, after a few twists and turns, the project was completed in February 1988.

LEP's other civil engineering feat was its precision. The components of the accelerator, the magnets and cavities, had to be positioned to within 0.1 millimetre of one another. This required excavating a near-perfect tunnel using tools and techniques that were at the cutting-edge of technology.

At the same time as LEP was approved and built, an experimental programme was set up. Interest was considerable, but only four experiments could be approved. The organisation of these experiments, known as the “LEP Model”, was a first in terms of large-scale international collaboration, with groups from all over the world taking part.

Recollections

In the beginning, LEP met considerable opposition in the nearby population […] To improve this situation, many senior CERN staff members spent an incredible amount of time giving lectures in all the neighbouring villages.

Herwig Schopper

Herwig Schopper came to CERN in the early 1970s to head the Nuclear Physics Division. Then, after chairing the directorate of the German nuclear research centre, DESY, for several years, he returned to CERN in 1981. He was Director-General of CERN from 1981 to 1988, during which time the Large Electron Positron (LEP) collider was approved and constructed.

“My first personal experience with LEP was a rigorous examination in the Committee of Council. One delegation was against my nomination as Director-General, suspecting that I would favour the German DESY site for LEP instead of CERN. After I had explained my intentions, the delegate concerned received new instructions by telephone during a coffee break; I was elected unanimously and the approval procedure for LEP could start.

While the approval of LEP was still pending, Margaret Thatcher visited CERN. On her arrival she told me that she wanted to be treated as a fellow scientist and not as Prime Minister. She surprised me with the question of why we intended to build a circular machine instead of two opposing linear colliders, a very pertinent question and proving her excellent briefing for the visit.

Indeed, it is a delicate matter of optimisation which of the two options is more favourable for a certain beam energy. I explained to her that in the case of LEP a circular machine was more cost effective. She accepted the argument and asked how big the tunnel would be for the next project after LEP. To my reply that the LEP tunnel would be the last ring at CERN she retorted: “Why should I believe you? When I visited CERN the first time John Adams told me that the SPS tunnel would be the last.” Nevertheless, she stated at a press conference that she had been convinced that the funds at CERN were used efficiently, and subsequently the United Kingdom approved LEP.

In the beginning, LEP met considerable opposition in the nearby population. We discovered that this was due to a lack of information, many people believing that the ‘N’ in CERN had something to do with nuclear power. To improve this situation, many senior CERN staff members spent an incredible amount of time giving lectures in all the neighbouring villages.

However, I was particularly worried when Denis de Rougemont, a well-known Swiss writer, published articles claiming that LEP was inhuman, gigantic and not necessary for society. This was a surprise since de Rougemont had founded the “Centre européen de la culture” immediately after the war, where politicians discussed how European scientists could learn to work peacefully together again. This political initiative, little known, was one of the channels that led to the foundation of CERN, the other one originating from physicists. I invited de Rougemont to lunch where we discussed his objections; in the end we resolved the difficulties, and I promised to explain his essential role for the creation of CERN at a public debate.

We always tried to take decisions on the basis of rational arguments. However, in the case of deciding on the location of the two experiments ALEPH and DELPHI, this method failed. So, it was agreed that a coin would be flipped. At a Directorate meeting, this act was performed in the presence of the two spokespeople, Jack Steinberger and Ugo Amaldi. After tossing the coin, Jack, being a very careful experimentalist, checked whether the coin had indeed two different sides.”

----

This interview is adapted from the 2004 book “Infinitely CERN”, published to celebrate CERN’s 50th anniversary. Schopper recently celebrated his 100th birthday, watch the recording of the dedicated symposium at CERN and read his recently published open access book that is both a memoir and a biography.