CERN70: Announcing the Higgs boson discovery

31 October 2024 · Voir en français

Ask any member of the particle physics community where they were on 4 July 2012 and they won’t need to think too hard about it. The discovery of the Higgs boson was a milestone in the history of science, as evidenced by the media tsunami that it caused.

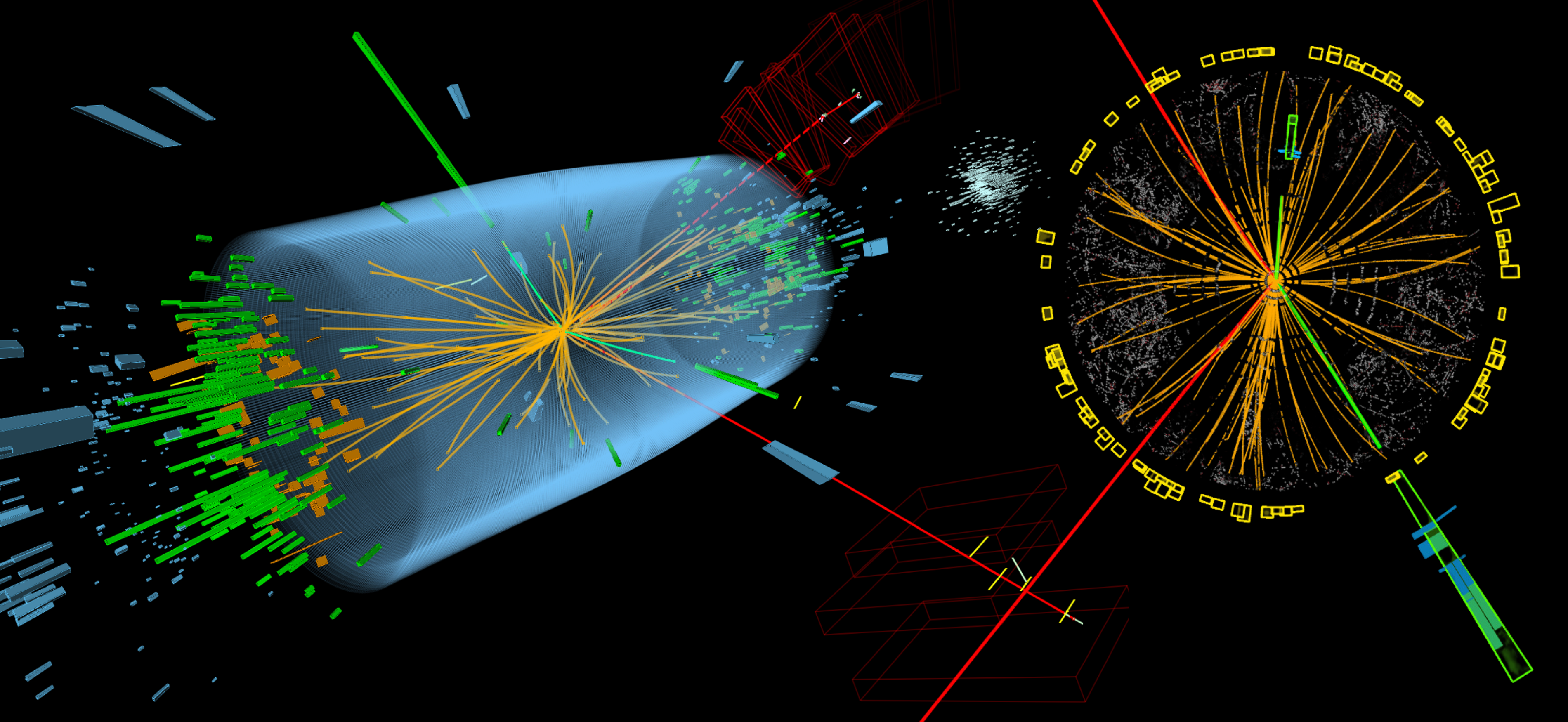

At 9.00 a.m. on 4 July 2012, Joe Incandela and Fabiola Gianotti, the spokespersons for the CMS and ATLAS experiments, took the floor one after the other in front of an excited audience to present the latest data from their experiments. No news had yet been released, but all of the experts were anticipating a spectacular announcement. The conference was broadcast in dozens of institutes around the world. In the United States, scientists woke up in the middle of the night to attend the event, on a bank holiday no less. At 10.40 a.m., thunderous applause erupted in CERN’s Main Auditorium, Peter Higgs shed a tear and the Director-General, Rolf Heuer, declared: “As a layman, I would say: now we have it!”. The results were unequivocal: they revealed the presence of a particle whose properties matched those of the Higgs boson, a particle that had been predicted 48 years earlier.

The story starts in the 1960s, when physicists began to realise that the electromagnetic and weak interactions (two of nature’s four fundamental forces) might be described by the same mathematical structure. A major challenge in building this unified “electroweak” theory, which is now a pillar of the Standard Model of particle physics, was that its equations demanded that the mediating particles of the interactions have zero mass, which would imply that they have an infinite range. But while the photon, the vector of the electromagnetic force, is indeed devoid of mass, this can’t be the case for the carriers of the weak interaction, as this interaction has a very small range, on an atomic scale.

The solution to this problem lay in work published earlier by the Belgian theorists Robert Brout and François Englert and, independently, the British theorist Peter Higgs. Taking inspiration from extensive research work – in particular, work on superconductivity – they had proposed a mechanism that, when it was applied by Steven Weinberg to the electroweak theory, enabled the mediators of the weak force to gain mass while ensuring that the photon of electromagnetism did not. The mechanism had two profound implications: the existence of the Z boson (a further carrier of weak interactions, in addition to the W boson), and the existence of an invisible field that permeates the entire Universe, with which more familiar particles such as electrons interact to gain their all-important masses. Indirect evidence for the existence of the Z boson was obtained at CERN in 1973, and both the W and Z bosons were finally discovered at CERN a decade later, their masses being as predicted by the electroweak theory. The existence of the Brout-Englert-Higgs field remained to be proven and, to do that, the only hope was to detect the associated particle, known as the Higgs boson.

After the attempts of the experiments at the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP) at CERN and at the Tevatron at Fermilab in the United States, the boson hunters placed all their hope in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which has been generating higher-energy collisions since 2010. At the end of 2011, the two general-purpose LHC experiments, ATLAS and CMS, presented promising early results that were nonetheless still inconclusive. The LHC restarted in April 2012 at a slightly higher energy after a technical maintenance stop in the winter. Data quickly revealed the presence of a particle with properties that matched those of the long-sought Higgs boson, which culminated in the announcement of 4 July. One year later, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded jointly to François Englert and Peter Higgs. The Nobel academy mentioned CERN and the ATLAS and CMS experiments in the statement accompanying the prize.

Since the discovery, the two experiments have carried out a lot of work to define the new particle. For the Higgs boson is an exotic item in the particle zoo. As the only known elementary particle with zero “spin”, it could potentially shed light on profound open questions in fundamental physics – ranging from the decoupling of the electromagnetic and weak forces immediately after the Big Bang to the ultimate stability of the Universe. That’s why 4 July 2012 marked the start of a new adventure for particle physics.

Recollections

Those weeks in June 2012 were memorable: lots of emotion, lots of pressure, people working day and night. There was such an electricity, such an exciting atmosphere!

Fabiola Gianotti

Fabiola Gianotti came to CERN as a research physicist in 1994. She was spokesperson of the ATLAS experiment at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) from March 2009 to February 2013. On 4 July 2012, alongside the CMS spokesperson at the time, Joe Incandela, she announced the discovery of the Higgs boson. She has been CERN Director-General since 2016.

“It was 2012 and, as we usually do in our field to avoid biases, we had “blinded” a relatively small mass region that had not been excluded by previous searches for the Higgs boson. All of our analysis optimisation, Monte Carlo tuning, etc., was done outside this region. At the beginning of June 2012, we were ready to unblind our results for the Higgs to gamma–gamma channel.

I was at Fermilab in Chicago the day of the unblinding and I emailed one of the conveners, asking “Did you unblind? What did you find? Send me a plot.” He did and there it was, an excess at a mass of around 125 GeV, at exactly the same position as the hints from the 2011 data! I replied “my goodness”, to which he responded “indeed”. It was a very short exchange, just three words: we both knew that the Higgs boson was there.

Results in only one channel weren’t enough for a robust discovery claim. If it really was the Higgs boson, we had to see a handful of events in the four-lepton final state. We had nothing at the beginning of June. But all of a sudden, in the second half of June, candidates in the four-lepton channel began to pop up. The CMS collaboration had promising signals in the same mass region and, as spokespersons of the CMS and ATLAS collaborations, Joe Incandela and I shared our preliminary results with the then Director-General, Rolf Heuer, and began to prepare for an announcement. Joe and I were in contact daily. I knew what CMS had, he knew what ATLAS had, but we never disclosed this to our collaborations to avoid increasing the pressure and introducing any bias.

Those weeks in June 2012 were memorable: lots of emotion, lots of pressure, people working day and night, eating pizza at 3 a.m. at CERN. There was such an electricity, such an exciting atmosphere! The LHC was working fantastically well, delivering large amounts of data daily, and we had put in place fast-track procedures to calibrate and analyse data almost immediately. Despite the emotion and pressure, we were extremely focused, and we did zillions of checks and cross checks. It was an immense amount of work, done in a very short time. What really surprised me was that, despite the result at stake, no-one in the ATLAS or CMS collaborations – almost 6000 people – disclosed our findings. It was a strong sign of our responsibility, commitment and integrity.

On the morning of 4 July, I got to CERN and saw the crowds of people trying to enter the Main Auditorium. The room was so packed.

Joe Incandela spoke first. I remember that while he was showing his slides, I thought with gratitude of the thousands of colleagues that had worked on ATLAS, CMS and the LHC over the decades and all the people that had made the LHC and its experiments possible. Some of them were no longer with us to see such a great accomplishment.

When I started to speak, I looked at the audience and spotted a few ATLAS colleagues who became my reference points during the talk. They were looking at me with such intensity, and they really gave me strength and energy. The room exploded into a big round of applause when I announced the five-sigma significance. Straight after the presentations came the press conference. This all happened on a Wednesday, and Wednesday meant the LHC Machine Committee (LMC) meeting, which I always attended. So, I was there, of course, as on every Wednesday. I remember Mike Lamont, who was machine coordinator at the time, was very surprised to see me on that special day. He started his report with a slide that said: “Status report from the Higgs factory”.

Finally, after a long and exhausting day, I went home and packed for the International Conference on High Energy Physics (ICHEP) in Melbourne. My flight was early in the morning on 5 July. At 3 a.m., I woke up suddenly, realising that Australia is on the other side of the globe and I’d packed for summer not winter. I quickly repacked in the middle of the night! The next morning, I walked onto the plane, past the table of newspapers, and all the front pages showed the Higgs boson discovery. I thought, “oh my goodness, we are everywhere” and then fell fast asleep for most of the flight! The adrenaline had evaporated all of a sudden.

At ICHEP, everybody was excited, but very quickly we got back to business discussing the next steps. The 4 July announcement was just the beginning of the huge work that followed to understand a very special particle, which is still ongoing today.

It was an immense privilege to be the spokesperson of an experiment at the time of a monumental discovery. A discovery is teamwork, the result of decades of hard work by physicists, technicians, engineers and other personnel. I was representing this great community. I could feel that strength on 4 July 2012.

----

More information about the search for the Higgs boson and the research carried out since its discovery can be found in the Higgs10 series published in 2022, on the tenth anniversary of the discovery.