Out of 292 proposals for CERN's first ever "Beamline for Schools" contest, two teams of high-school students – Odysseus' Comrades from Varvakios Pilot School in Athens, Greece and Dominicuscollege from Dominicus College in Nijmegen in the Netherlands – were selected to spend 10 days conducting their proposed experiments at the fully equipped T9 beamline on CERN's Meyrin site. Dedicated CERN staff and users from across the departments have put in a huge effort to ensure the success of the project.

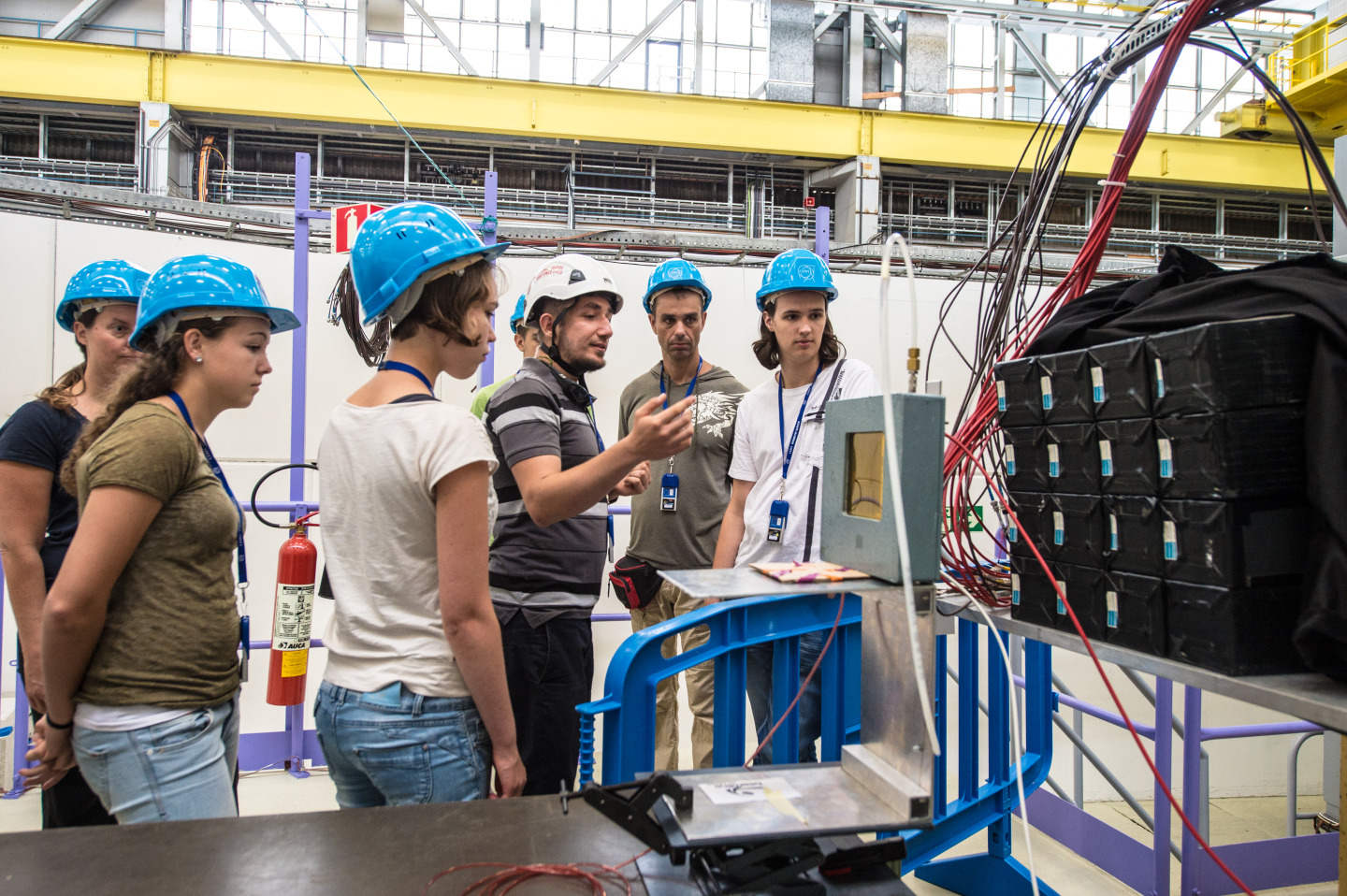

It's finally beam time. After months of organisation, coding, engineering and even painting the experimental area, the T9 beamline is ready to deliver protons to experiments devised and built by high-school students. “They are here to collect data and experience the life of a scientist. I don't want their time here to feel like a planned VIP visit," said Christoph Rembser, the Beamline for Schools project coordinator. “We will adapt to changes as they come up just as experimental physicists do on shift and, if there is downtime, the students will have a chance to visit some CERN installations such as CMS and ATLAS.”

The students' first full day at CERN was devoted to safety awareness and training. The teams learnt to recognise hazard signs and safety protocols at CERN, and members of the HSE Unit, the Cryogenics Group and the Fire Brigade gave presentations about staying safe at CERN.

Now it's over to the beamline. For veteran beams physicist Lau Gatignon, who is instructing the students in basic beam physics, the project is a welcome novelty. “Beams have been keeping me busy at CERN for 35 years, but this is the first time I’ll be working on a beamline with a bunch of 16- and 17-year-olds," he says. "The students are very excited; it’s great to see!”

The two teams of students come from Greece and the Netherlands. The first one, Odysseus’ Comrades, a team of 12, will look at the decay of charged pions to investigate the weak force. "We wanted something simple but understandable that would be connected to the history of CERN," says team member Konstantinos Papathanasiou (17). "We had to learn a lot of new things, but now we understand the necessary physics." The Dutch Dominicuscollege, a team of five, have grown their own crystals to make a calorimeter and test it with the beam at CERN. The team came up with the idea after two students attended a course in crystallography at Radboud University in Nijmegen. “We learnt about X-ray crystallography and crystal structure," says Lisa Biesot (17). "We thought that using crystals for the experiment was a great idea,” says Olaf Leenders (17). Their calorimeter will also be used as a component in the pion-decay experiment, making the beamline project a truly international and interdisciplinary experiment, like all typical experiments at CERN.

In order for the two teams to run their research projects, a lot of CERN scientists have worked to prepare the T9 beamline and have offered guidance during the experimental phase at CERN. Detector physicists Cenk Yildiz and Saime Gurbuz are among those scientists: they have spent weeks writing data-acquisition software and have been training the students on site in the specifics of data acquisition and of taking shifts. "We are using terminal commands and the Linux system, for example, which may be unfamiliar to the students," says Gurbuz. "But they are very hard-working! They have studied their lessons; when I ask them questions they answer straight away!"

"The experiments these young students have designed and run are challenging," concludes Rembser. "I will encourage them to write a paper at the end for the real science experience, but we will have to see how it goes!"